“When we create software,” Samuel Hulick wrote, “we’re not creating a tool, we’re creating an environment for accomplishment.”

In this post, let’s hold Samuel’s assertion up to the light, and find out what happens when ‘Environments’ speak with ‘Human behavior.’

Before we get to that, I’d like to propose a brief tour, a visit to an afternoon at work.

****

As though they’re mindful of our demanding schedules, most afternoons slip from the calendars, unnoticed. This particular August afternoon, though, denied that compulsion.

Its base ingredient was pleasantness.

Sunlight, distilled, first by the clouds and then by the accidentally stained window glass, brought with it, a kind of day when one expects to do a lot. A pretty day.

But a teammate’s forehead staged a different story.

He was anxious. Concerned about a tool that had failed him repeatedly. In this case, just for a few seconds, it had stopped him from sharing something he had worked on, over the weekend.

It was the browser.

It had surrendered to its own doing. Too many tabs. The ensuing crash stripped the air of its capabilities, and triggered a lament from the said teammate, who himself, is involved in the making of such tools.

“I can’t help it. This always gets out of control. I don’t know. Maybe, it shouldn’t let me!”

Routine reigned. The browser was up again. The teammate’s mood took some mending. He did share the progress on his work. It was fine, a parcel from a Sunday spent reflecting.

Every workday contains its fine share of similar rough encounters.

One way to think about them, is to say that it’s never about the tools. And it’s always about the people.

Because: first, we get to control what a tool does, and second, if a tool fails, it’s up to us to not perceive the event as the end of the world.

Another way to assess these encounters is to acknowledge that these interactions with tools, with their form and their function, the typography and the colors, the error messages and the progress bars, leave an imprint – however inconsequential it might seem – on how we think.

At best, a rough start to a presentation, or a day, or a week; at worst, something more paralyzing, something that author and design impresario, Don Norman, calls taught helplessness.

Put forth in the same pedigree of trouble as a known psychological phenomenon called learned helplessness, which stems from one’s repeated failure at a given task, making one believe “that the task cannot be done, at least not by them,” and that “they are helpless.”

This is followed by a loss of faith in future attempts, and if the feeling persists and “covers a group of tasks, the result can be severe difficulties coping with life.”

Don notes that “the design of everyday things seems almost guaranteed to cause this.”

This is just the opposite of the more normal situation where people blame their own difficulties on the environment. This false blame is especially ironic because the culprit here is usually the poor design of technology, so blaming the environment (the technology) would be completely appropriate.

Such failures are direct, though. We can retrace their steps with little discomfort.

It’s the subtle discourse that takes place between our thoughts and the cues that tools (our immediate environment) hurl at us, that gets way more perilous.

****

The forte of most tools is repetition. Doing what they’ve always done.

In that sense, a clock’s tick-tock, a bot’s timely prompt, and the shape of our continents, are all alike. Always around, doing their thing, slowly powering a series of transformations.

This particular ‘repetition’ that hails from our environment, informs our lives as much as the ‘repetition’ that resides in our own habits. And being ground between the two, shapes human behavior.

In the following paragraphs, we’ll see how the unchanging order of our environments (agriculture), changes us. We’ll see how we shape (cities) it back. And then, what happens when both culminate (web based software).

****

The power of the dead is that we think they see us all the time. The dead have presence. Is there a level of energy composed solely of the dead? They are also in the ground, of course, asleep and crumbling. Perhaps we are what they dream. May the days be aimless. Let the seasons drift. Do not advance the action according to a plan.

Given enough time, inanimate things in our environment, attain a similar aimlessness that White Noise’s protagonist ascribes to the dead. The keenness with which they were once met is lost. Their effects on us, vanish.

Or do they?

An environment is, as we’ll learn, the often ignored postscript to mankind’s letters of what ifs and whys.

Professor Jared Diamond took up the pen to write Guns, Germs, and Steel, to answer a daunting question, “Why did history unfold differently on different continents?”

He arrived at a part of the answer based on two facts about the prevailing environment: the availability of wild plants suitable for domestication, and the shape of our continents.

While having lunch, wouldn’t it be a thing to learn that our food could be almost as ancient as the dust motes aswirl in the air?

It is.

The major crops (wheat, barley, etc.) that thrive today, have been around ever since they were first discovered about 10,000 years ago.

Of the thousands of wild plant species that are edible, only a few can be cultivated. The mere existence of these crops in certain areas on earth gave these areas a head-start.

A geographic lottery.

While the transition to agriculture in the Middle East and Central America, began in 9000 BC and 3500 BC respectively, places like Australia and South America didn’t get to witness it until the last few hundred years.

Furthermore, it wasn’t just the discovery of edible crops but also the speed at which they were adopted, that mattered. And that depended on the orientation of continents.

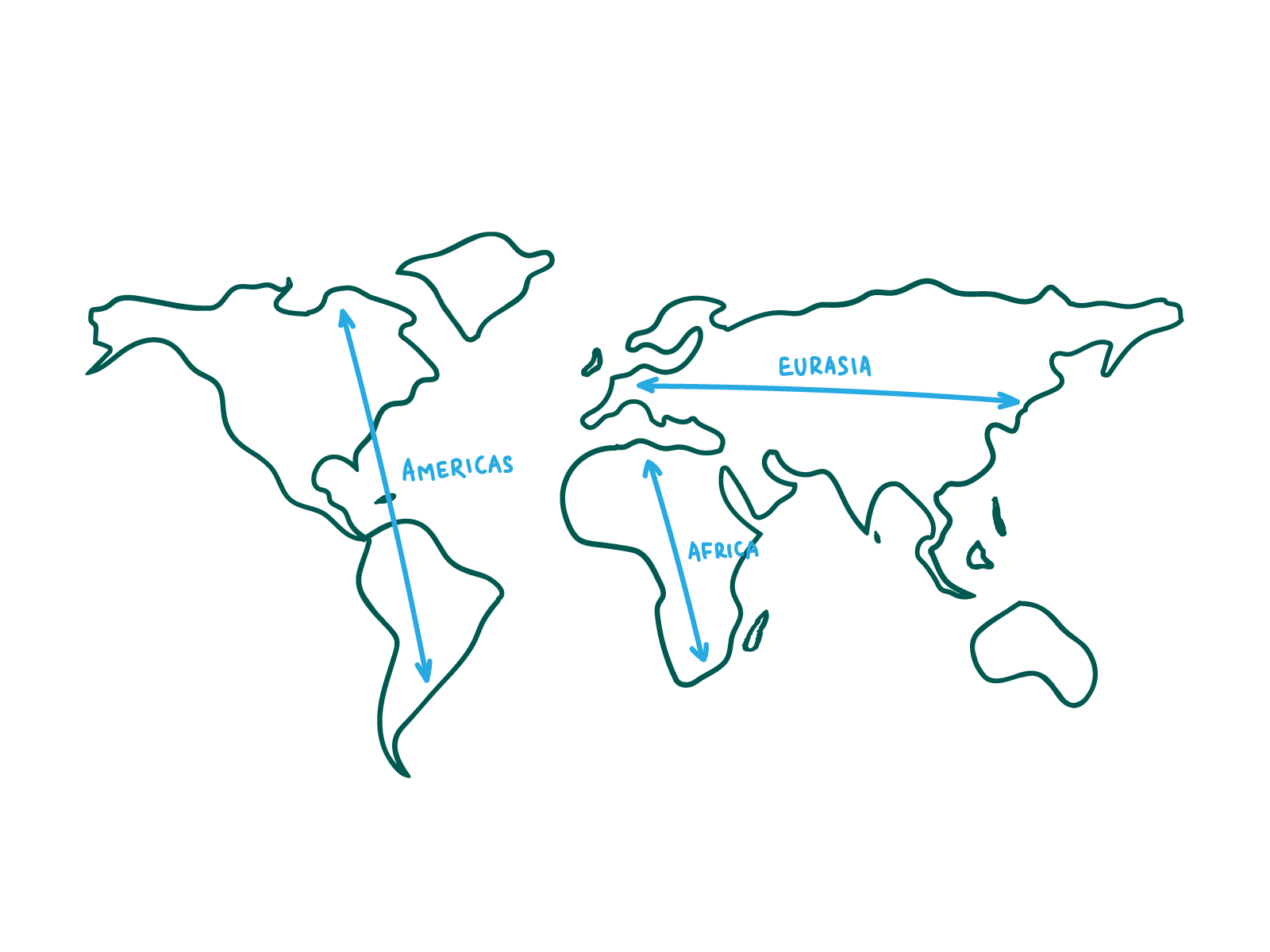

As any map would tell you, the primary span of Eurasia, is east-west. And that of the Americas and Africa is north-south. How much of an impact could that possibly have?

Unimaginable.

Localities distributed east and west of each other at the same latitude share exactly the same day length, and its seasonal variations. To a lesser degree, they also tend to share similar diseases, regimes of temperature and rainfall, and habitats or biomes (types of vegetation).

The accidental domestication of crops by a band of hunter-gatherers somewhere in the middle-east, landed in neighboring regions at an average of 0.7 miles per year, compared to the the spread of crops from Mexico northward to the U.S southwest at a mere 0.3 miles per year.

The regions where agriculture arrived first, civilizations, steel, arts, and almost everything else that we equate with human progress arrived first.

As the Israeli historian, Yuval Noah Harari writes in his revelatory landmine of a book, Sapiens, “We didn’t domesticate wheat. It domesticated us.” It changed us.

Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior. We tend to believe our habits are a product of our motivation, talent, and effort. Certainly, these qualities matter. But the surprising thing is, especially over a long time period, your personal characteristics tend to get overpowered by your environment.

The transition to agriculture was an offshoot of one kind of environment. With irrigation tools, dams, and villages, we constructed another kind.

An environment that relied heavily on this new model of living. We became settlers. Populations soared. So did needs, and our excavations for more resources.

There was no going back.

Tales of a city

There was a building on thirteenth street, and it was a… I remember it was a red building. Some lunatic had painted the whole building red. Perfect! Because that’s a precursor to a lot of blood is going to be shed. That obvious a choice. You don’t notice it. You don’t remember it when the blood starts to be shed but it’s part of a palette that I have to use in making a movie. – Academy Award winning director Sidney Lumet, describing how he zeroed in on a location for a scene, in his 1973 film, Serpico

Sydney’s thoughts speak for the deliberations involved in making a scene work, just the way he imagined it, “in both places, heart and mind.” A director’s method of chiseling the environment to fit a vision that moves actors, and as a result, an audience.

These thoughts also speak for the carving of a city’s environment – in fact and fiction – by precursors. Buildings, billboards, and other structures that move, in this case, a different cast of actors, the city dwellers.

Unlike Sydney, though, the makers (directors) of a city, are seldom aware of these precursors, and their impact on generations.

Back in the 1990s, New York witnessed a drastic decline in crime rates.

It was ascribed to various possible reasons:

- the decline of the unemployment rate by 39% between 1992 and 1999

- vanishing crack outbreak

- increase in the number of police officers per capita

- police’s focus on smaller crimes

- increase in the prison population

- legalization of abortion

- and fixing broken windows

“Fixing broken windows” was about fixing the surroundings. It originated from a social science theory that stated that if a broken window in a house is left unattended, passersby will break more windows.

And that, in turn, will trigger a cycle of bad behavior (from breaking in, to drug dealing, to more violent crimes). The notion that disorder in the environment breeds disorder in its inhabitants’ behavior.

Its execution translated into the removal of graffiti from subways, drug trade in abandoned buildings, and the tiniest symptoms of unruly acts from the streets. Enforcement located itself, first in embankments, and pillars, and parks. And then, in people.

The best way to deal with such issues? Are things better for everyone, as a result?

Studies, statistics, have gone on to prove that this works. But, when it comes to a city’s design, it’s also worth considering the role played by a powerful few.

Few individuals have influenced the making of cities as much as the urban planner Robert Moses influenced New York. The provenance of Moses’ influence could have been the oxygen of pure competence.

But as Robert Caro observes in his classic, The Power Broker, Robert Moses, “displayed contempt for people he felt were considerably beneath him.” This contempt made its way into his creations.

His architecture was an architecture of exclusion. To avoid the passage of buses through certain areas, the bridges were designed to be low.

Parks. Tunnels. Imagine everything designed with the same lens. Imagine the number of people who missed out on library visits, strolls on beaches, and the possibilities of a better life. Imagine the number of sepia postcards that were never sent.

Wantagh State Parkway – New York, Source

Wantagh State Parkway – New York, Source

Moses used his power as an architect to make it physically difficult for certain individuals to reach the places from which he desired to exclude them. Although in this situation, there was at least anecdotal evidence of the architect’s intent, that sort of evidence is often not available. Instead, our environment contains low bridges that might make travel difficult for some, but we tend to view such bridges as innocuous features rather than as exclusionary objects.” ~ Sarah Schindler, Architectural Exclusion: Discrimination and Segregation Through Physical Design of the Built Environment

A man deciding the fate of millions. That fact rings an ominous bell for us digital denizens. A few makers get to decide how millions, at times billions, spend their mornings.

The ideals of a city mirror that of an open web. Contribution is its currency. The complexity of networks and the cross pollination that it leads to, are its drivers.

Just like the feedback mechanisms of modern software, a city has an army of silent learners, like the walkways that have known generations of footsteps and the theaters that have seen what makes a story work.

A city, just like the internet, has an appetite for what’s about to come, at the same time a longing for what was.

But it’s always in flux. Always learning. Taking directions, and then directing us back.

Software and small talk

A man has insomnia. He turns over in bed, he recaptures his impressions and hallucinations of half-sleep, some of which have to do with the difficulty of getting to sleep when he was a boy in his room in the country house of his parents in Combray. Seventeen pages! Where one sentence (at the end of page 4 and page 5) goes on for forty-four lines.

Working for a publisher named Fasquelle, Jacques Madeleine had to reach the higher registers of his analytical mind, to discern the pages of a manuscript that would become Marcel Proust’s generous gift to literature, In Search of Lost Time.

The above quote illustrates a part of Jacques’ discontent with Proust’s novel, and similar observations led Fasquelle, and many other publishers to reject the possibility of its publication. The piling up of rejections didn’t deter Proust, as he paid for the publishing himself.

As Alain De Botton reminds us in his wonderful book, How Proust Can Change Your Life, Marcel Proust made a choice, and took his time with the novel, and even other things like laying his attentive eyes to a homicide report in the newspaper.

A tool that’s been about taking one’s time is a book.

“Books are sharks,” Douglas Adams once told Neil Gaiman, “They’re solar powered. If you drop them, they keep on being a book.”

Sometimes with sudden ferocity, sometimes with slow nudges that possess the sweetness of bedtime cookies, books can move us into new worlds. And that occurs because we decide to contain our attention in the service of reading one word at a time.

Back when the printing press was invented, this behavior wasn’t the norm.

What the book does as a technology is shield us from distraction … suddenly we see this very immersive kind of very attentive thinking … and what we know about the brain is that brain adapts to these types of tools. So, then, the ways of thinking that we learn from tool, we can then apply in other areas of our life. So, we become, after the arrival of printing press in general, more attentive, more attuned to contemplative ways of thinking.

In the age of distraction, how many of us get to make Proust’s choice with our life and our work? How many tools empower us to take our time?

To finish that side project. To get into a deep a conversation with a teammate. To spend hours listening to a 5 year old describing her first attempt at dismantling a cuckoo clock.

Increasingly, our immediate environment is made up of screens of all stripes. They flood over us with their demands, leaving the mind’s door open for mental debauchery.

First thing to pay attention to are the kind of choices that a screen offers, and how those choices stack up against our values.

Joe Edelman has done some admirable work of imagining what an ideal day on the web could look like, and the steps we could take towards it. Imploring us to optimize our products not for time spent, but for time well spent.

His work is centered on the idea that we’d be better off, if software made it simpler for us to make as few regrettable decisions as posible.

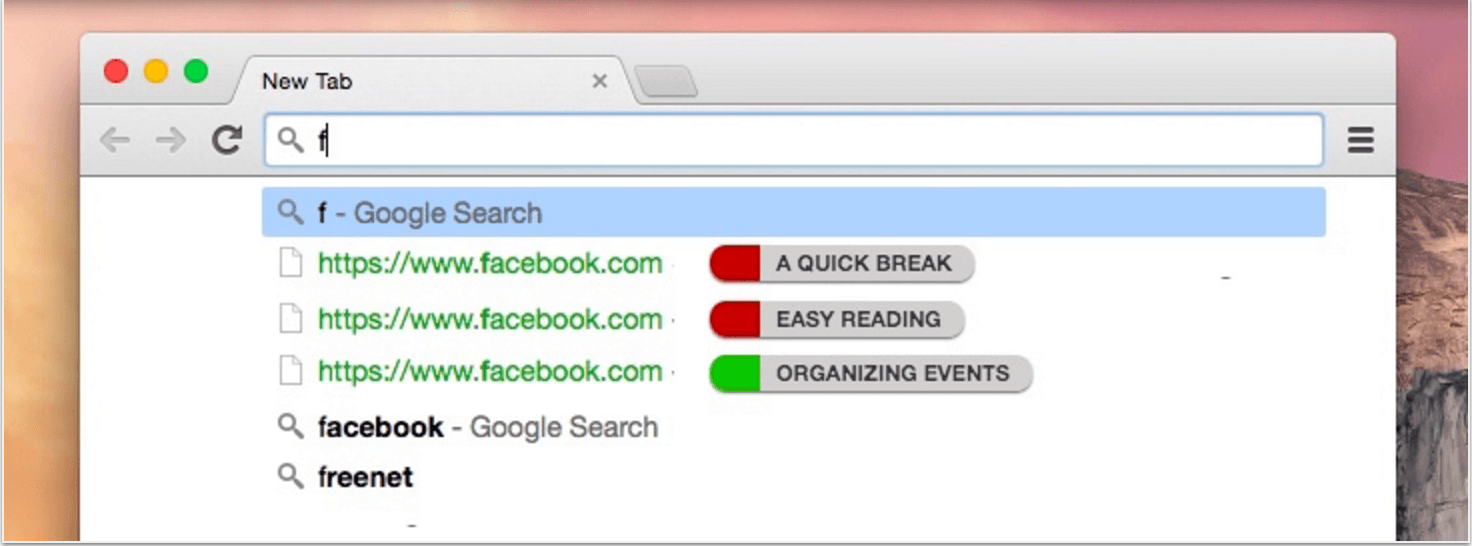

Wouldn’t the browser window be less menacing if it told us what, exactly, a URL would be about, and as a result, nudge us to take a moment to see if that fits our goals? We might or might not make the right decision, but at least we’d know that we were offered a choice.

An imagined browser experience aimed at informing better choices.

Can we measure demand with the question “what are you glad that you bought?” instead of “what did you buy?”, or online, with “what are you glad you clicked?” rather than “what did you click?” Can we tether the lifeblood of our economy – cashflow, attention, and resources – to reports of informed and fulfilled lives? Would people then work together to create the best outcomes for one another – in much the same way they currently collaborate to generate sales, clicks, and views?

The other thing to understand is the importance of what passes unseen in the interfaces, the effects of fonts, colors, and words, that end up informing our taste, and our ability to imagine. Hence, the question of aesthetics.

We need good design in the world, not because we want to be extravagant or superfluous, not to get people to buy more stuff, but because good design helps us to be the best version of ourselves.

Poet and essayist, Joseph Brodsky said, “On the whole, every new aesthetic reality makes man’s ethical reality more precise. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics.”

In our search for the ultimate human experience, this is truer than ever. MailChimp’s Aaron Whitehead observed “trying to design usable interfaces is like a chef trying to create edible food.”

One could cite that the Futura font makes the headline stronger, and that the Baskerville font makes the transcribed speech feel much more reliable, or that a SaaS app, tinged with just the right kind of orange, makes the experience cheerful.

But all of that springs from something more powerful, a special intent that makers possess, and the things they do to make sure it shows up in their creations.

The intent to make life a little better for the humans who’re using their products. What’s common between the way Pixar deals with stories and the way Wufoo, and now Typeform, deal with forms, is precisely that intent.

The inspiration for our color palette did come from our competitors. It was really depressing to see so much software designed to remind people they’re making databases in a windowless office and so we immediately knew we wanted to go in the opposite direction.

Crew’s Mikael Cho recently wrote about the merits of placing substance over beauty. He is right. But given the luxury of constant iterations, why can’t we aim for both?

Even Crew’s own work is an exemplar of the same.

Substance and beauty. Care and effort. And a bit of small talk.

Small talk has always seemed to me, a lifelong chore. Part of the reason is my aversion to news, and also the lack of vision in imagining the substance that lies in incessantly talking about the weather.

From the countless “oh, yes-es” I’ve amassed from conversations, I’ve always asked myself: why can’t we start a conversation with the main thing, if we’re going to get there anyway?

But ever since I’ve come across the following passage in an essay, there has been renewed interest in kickstarting new experiments with small talk.

Every speech act is an act, meant not only to communicate something but to do something: reassure, acknowledge, nurture, enjoin, reject, dominate, encourage, or just fill awkward silence. We can think of this as the social function of a speech act.

David asserts that “speech says things but also does things.”

Software makers can take a page.

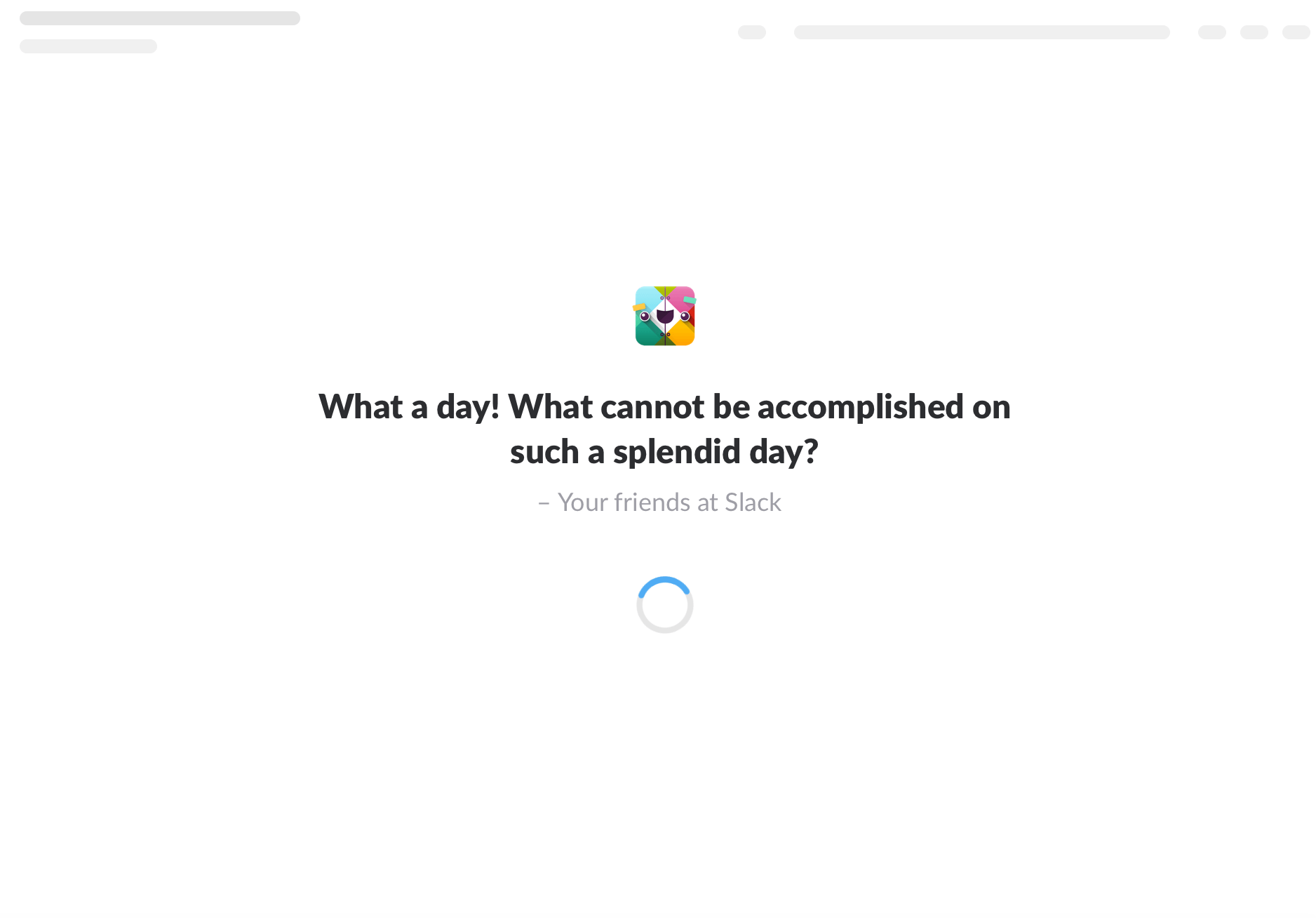

A collaboration tool shouldn’t just do what it does, but it should also encourage us to remember that there will be tough days and that we have to hang in there.

From Dudeism to Brene Brown’s dispatches on courage, an encounter with Slack’s inventory of loading messages is always gladdening.

A billing app shouldn’t just bill. It should reassure us that everything is taken care of, and that nothing would break.

Can this encouraging and reassuring from the environment, trigger us to do the same?

One may liken this to tuning in – subconsciously or consciously – to a special radio station run by the environment that only broadcasts song intros, and we get to make the chorus and the rest of the verse by ourselves. The song intros of empathy, when produced with care, are worth everything.

For it was empathy, as this study suggests, that led settlers in America from Africa, Germany, Russia, and other parts of the world, to better their emotional expressions, “in order to compensate for a lack of common norms and language.”

Small talk has its roots in empathy.

And I’m certain that our environment could use a dollop of it, every day.

They’ll do it anyway

“There are three relations. One is to what surrounds you. One to the divine cause from which all things come to pass for all. One to those who live at the same time with you.”

No matter what the environment is like, in the end, it’s our perception that determines what we make of it.

The air of 1920s didn’t exactly equip women with hope. The strange phone call that offered her a chance to become a part of the first transatlantic flight was anything but promising. But Amelia Earhart did it anyway.

Malcolm X entered a Massachusetts state prison on burglary charges. In a place tainted with suffering and bad behavior, he found books, and because of them, true freedom. Taught himself to read. Then, read everything in the library. The prison became his university.

Then, there’s this man:

You see, people will figure it out.

But as those who make and sell tools, it’s still our responsibility to envision better products, and better environments, and hope that the goodness drawn from that, might just remind humans who use these tools, to put kindness over convenience more often.

****

“It would be fatuous to assume that every man is constantly aware of the details of his surroundings. I do not believe this to be true.But I am convinced that a well-set dinner table will aid the flow of gastric juices; that a well-lighted and planned classroom is conducive to study; that carefully selected colors chosen with an eye to psychological influence will develop better and more lucrative work habits for the man at the machine; that a quietly designed conference room at the United Nations headquarters might well help influence the representatives to make a calm and just decision.

I believe that man achieves his tallest measure of serenity when surrounded by beauty. We find our most serene moments in great cathedrals, in the presence of fine pictures and sculpture, on a university campus, or listening to magnificent music.

Industry, technology, and mass production have made it possible for the average man to surround himself with this serenity in his home and in his place of work. Perhaps it is this serenity which we need most in the world, today.” ~ Henry Dreyfuss, Inventor, Industrial Designer