Unhacking SaaS Growth and Rethinking

Recurring Billing's Role In It

A guide to make sense of growth, discover growth levers, and why recurring billing is more than a mere utility

Part of planning for growth is figuring out what your strengths are, so you can leverage them when the time is right. This guide presents a contextual approach to growth that will help you think about what your strengths are in relation to the five pillars of the customer lifecycle — acquisition, activation, revenue, retention, and referral. It makes a case for why this is better than isolating a growth metric or strategy or hack to pursue — each can lead to wins, but growth will stick only if you can turn sporadic wins into consistent ones.

Part of it is also figuring out if the weapons you are using will continue to work for you in the battles that lie ahead. To this end, this guide is a dive into the billing system — a powerful weapon in your arsenal — and how you can use it to accentuate your strengths and accelerate your growth.

The conceptual tension of 'SaaS growth'

"I have yet to see any problem, however complicated, which, when looked at in the right way, did not become still more complicated."

— Poul Anderson

Poul Anderson's sentiments are especially applicable today, talking about what might be the universal, top-of-the-mind problem of entrepreneurs everywhere — growth.

SaaS Growth is hard to think about, in my opinion, because there is tension within the concept.

The tension with definitions

It's true that growth can be defined (you're growing if you have more renewing customers than canceling ones and you're growing if your collective customer LTV is three times your collective CAC).

But it's also true that these kinds of definitions leave much to be desired: they're isolated, lagging indicators that fail to provide a holistic picture of what's working, what's not, and why.

The tension with properties

It's true that growth, across the board, is associated with the same properties. Scalability, repeatability, and predictability are forces that divide companies that crack under the pressure of scale from companies that are robust enough to push through growing pains into sustainability.

But it's also true that properties, like definitions, fail to tell you what's causing them to work and how.

Scalability might be driving growth but what's going right enough to cause it? Where? Sometimes it's even hard for founders to pinpoint why a product is blowing up.

The tension of blueprints

It's true that when a company is growing, you can tell. When Shopify jumps from making 205 million to 389 million in 365 days, you can break down what they might have done differently over the last year. When Slack's trial to paid conversion rate hits 30%, you can do the same.

But you can look at a company like Shopify or Slack, tell that they're growing, figure out the blueprint they used to do it, and still be in square one because your context is different from theirs.

Context seems to be the recurring cause of tension in the concept of growth, and rightly so. Companies have different goals and different amounts of resources (time, people, and money) to meet them.

Growth advice that doesn't account for this kind of context might be good enough for a win here and there but not much more.

'Levers' account for context

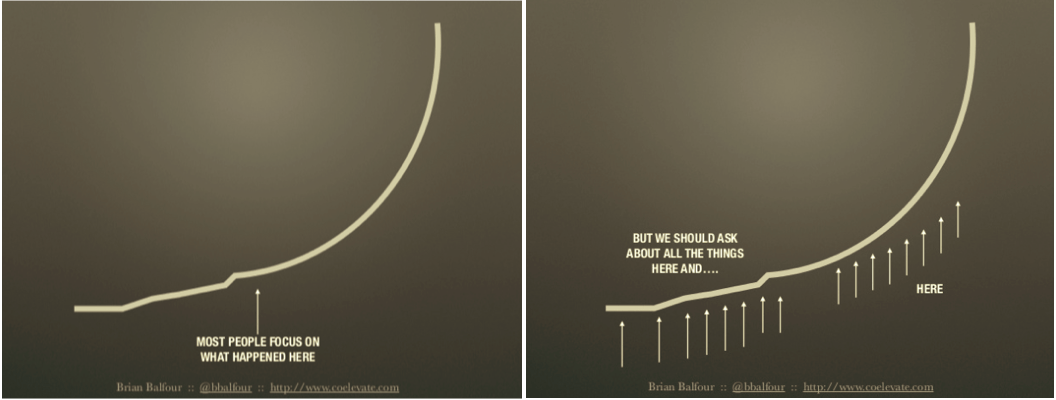

Brian Balfour, talking about the difference between gaining traction and pushing scale in SaaS, highlights what he calls 'growth levers' or strengths that can be leveraged for growth.

Growth levers have got more going for them than isolated strategies, properties or definitions:

- They acknowledge context. The only way that you can apply a growth lever you read about is to make it your own, factoring your own goals and resources into the picture.

- They can only be derived from what's working. If a revenue or a retention metric is doing well, and you can identify why, you've identified an advantage that you can exploit.

Growth levers can be diverse:

- They can be what sets you apart from your competition. Whether that is building a product for a certain kind of customer (Stripe started out building for developers, Snapchat built for teens), chasing a niche in the market only you can see, or something you're doing — your support or your in-app notifications — that is differentiating you from people who offer the same service.

- They can be a pricing or market strategy. You can derive growth levers from the market you're chasing (RedHat grew by going after a huge market with a big idea rather than a niche), the acquisition channels or word-of-mouth you're building, (NastyGal leveraged eBay to reach their audience) or the monetization strategy you're using for your product.

- They can be the unique way you're solving a problem. Take Spotify and Apple, for example. Both were really competing against piracy in the music industry. Apple solved for it with a pay-cents-per-track model, but ultimately, it was Spotify leveraging their powerful freemium listen-as-much-as-you-want model that beat Apple Music out in terms of paid subscriber numbers.

Growth levers are specific, acknowledge context, and play on your strengths, which definitely make them practical tools that you can work with.

But they're not the whole picture

Brian illustrates this point beautifully with a growth curve in his slideshare, Building A Growth Machine:

Growth levers aren't silver bullets.

The only way to leverage them is to think about the systems that they are embedded in.

Growth levers don't exist in a vacuum

You think that because you understand "one" that you must therefore understand "two" because one and one make two. But you forget that you must also understand "and."

— Rumi

Donella Meadows, in her book Thinking in Systems, describes a system as "a set of things ― people, cells, molecules, or whatever — interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time."

There are examples of systems all around us. They're so easy to see because of the tangible elements that compose them and the patterns they produce.

The digestive system is made up of teeth and tissue, acid and bacteria, muscle and movement, interconnected to digest food in a pattern of nutrition. The university system is made up of deans and professors, freshmen and textbooks, parties and student debt, interconnected to produce learning in a pattern of progress.

Growth levers are part of growth systems

Looking at Brian's growth curve, it's easy to think of SaaS growth in the same way — a set of things (your product, people, their mindsets, functions, and tools) interconnected in a way that produces (and sustains) patterns of growth behavior over time.

'Patterns that arise from the way elements are connected' is the link between a growth lever and actual growth.

Here's how.

Patterns make it easy to distinguish strengths (growth levers) > When you can identify strengths, you can create even stronger patterns around them so your wins are more and more consistent (than sporadic) over time > Growth.

In essence:

- If you see a growth lever that's working for someone else and want to try to it out, look at the patterns that exist in your growth system. How might the lever fit into them? What new patterns will emerge? The only way to fit a growth lever into your business is to experiment with it.

- Patterns help identify new growth levers. Looking at the patterns you have at the moment, consciously experimenting with them, creating new ones and experimenting with those, and keeping an eye on the numbers to see what's working.

Systems are made of subsystems

The question, now, is: How do you start experimenting with growth levers?

Seeing growth as a system can be overwhelming because of the number of moving parts, feedback loops, and emerging patterns to think about.

The answer is to break the growth system down.

Why it is necessary to see a system as made of subsystems

Thomas Starr and Timothy Allen tell the story of two watchmakers, Hora and Tempus in their book, Hierarchy Perspectives.

Both Hora and Tempus were fine craftsmen who developed watches that were composed of a thousand distinct parts.

Both their shops were filled with customers for a while but over time Hora got more and more customers and Tempus got less and less.

Tempus put his watches together in such a way that if he was distracted halfway through building one — to answer the door, for example — all the pieces fell apart, and he had to start from scratch. The more customers he got, the fewer watches he finished.

Hora did things a little differently. Though his watches were composed of the same number of pieces, he built in tens. He would build a group of ten elements that he would then organize into a larger subsystem, ten subsystems made the whole watch. Whenever he was interrupted, Hora didn't have to start from scratch and lost only a small part of his work.

What do the subsystems of a growth system look like?

The story of Hora and Tempus shows that subsystems can help organise patterns. To build a pattern in a subsystem makes it less susceptible to disruption.

What could the subsystems of a SaaS growth system look like, though?

In SaaS, the question of building subsystems is closely tied to the question of how you're going to measure their effectiveness.

The answer lies, as it does with most things in SaaS, with metrics. And metrics begin and end with the customer lifecycle — acquisition, activation, retention, revenue, and referral (from Dave McClure).

Let them be our subsystems.

An acquisition pattern might look like this: User discovers top of the funnel blog post on Google > user reads the post > user visits pricing page > user signs up for free trial

Or

User tries out a free tool you've made > user signs up for a product demo (three months later)

A retention pattern might look like this: user's payment fails > payment failure email sent out > card is retried and payment is automatically recovered > customer is successfully retained

Or

User's engagement inside the app is at an all time low > user signs up for webinar you've put together on customer success > user's engagement rises after the webinar

The options, permutations, and combinations are endless across AARRR (acquisition, activation, retention, revenue, and referral).

And experimenting with them is the only way to find out whether a growth lever (like freemium vs free trial in the acquisition subsystem or transactional email campaigns vs customer success webinars in the retention subsystem) is working or not.

A growth lever is only as powerful as the pattern it is embedded in.

Real world example: Freemium

Take a growth lever that accelerated growth for Spotify, SurveyMonkey, and Prezi: the freemium model.

It didn't for Baremetrics, Ning, and Bidsketch.

The answers to why aren't lurking within the freemium model itself but in the different systems, subsystems and connections that it was operating within.

Baremetrics

Let's take Baremetrics first. When they initially implemented a Freemium plan, users flocked to it. Over a thousand new accounts were created in the eleven weeks after they announced it.

The problem was that with a low free-to-paid conversion rate, they didn't have the infrastructure to support so many new users.

"We were dealing with day-after-day and week-after-week of progressively more complex server and performance issues as we just kept piling on the new free accounts." Josh Pigford, the founder of Baremetrics writes.

"To make matters worse, we were so focused on putting out server fires, we found ourselves making zero progress on the product itself."

This created issues in their retention subsystem. Churn followed as users faced delayed data, server downtime, sub-optimal support and a stagnant product.

They solved the problem by ditching freemium and switching to a fourteen day free trial — they stopped processing data if customers didn't upgrade in fourteen days.

Ning

Ning has a similar story: Freemium worked beautifully for their acquisition funnel — pulling in over three hundred thousand new users.

The problem was that Ning was converting only 5% of it's free users into paid customers.

"Low conversion rates aren't necessarily catastrophic", Taylor Buley writes, covering Ning's story for Forbes, "but Ning's freemium freeriders sucked down its most expensive resources — headcount, bandwidth and infrastructure — at a rate Ning could not support."

Ning's activation subsystem was suffering.

They solved the problem in two ways:

- A new pricing strategy that catered more to the B2B segment rather than the B2C and (a monetization revamp)

- Abandoning Freemium forcing free users to upgrade or else. (an activation revamp)

Bidsketch

Bidsketch's problem was worse — their conversion rates were around 1%.

"My user base was growing fast but the money was barely trickling in." Ruben Gamez, the founder, writes.

What separates Bidsketch from the other two companies we're looking at is how they experimented before they decided Freemium wasn't for them.

Ruben tried:

- Premium features for fifteen days before users got a downgrade to the freemium plan.

- Email campaigns pushing users towards paid plans and

- A smaller feature set on the freemium plan.

None of the changes had a big impact.

Ruben's user base continued to grow just as his conversion rates continued to plummet.

It got a point where Ruben just up and removed the free plan from his pricing page. He didn't tell anyone, he just did it.

And things started to move in the opposite direction. A five minute change led to 8x more paid conversions in the following week, and 10x more conversion in the rest of the month.

Learnings

We looked at three companies that experimented with a growth lever in their acquisition subsystems (freemium worked, in all cases, pulling users in) only to find that there were consequences in their activation, retention, and monetization subsystems that they just couldn't support.

Baremetrics' Josh Pigford, reflecting back on how he could have experimented with Freemium better, admits that Freemium could have worked for them with a little tweaking. With limited data imported into the system on the Freemium plan, for example. Or a full feature trial to begin with followed by a downgrade to the freemium plan. They just didn't have the time to run the experiments they wanted to.

Bidsketch actually ran the experiments that Josh wanted to at Baremetrics. All it showed Ruben, though, was that freemium wasn't working for his revenue. His conversion rates went up without it.

Ning was working with a better conversion rate than Bidsketch, but they had to do more than abandon freemium to get out of the revenue slump it created — they needed to pivot towards a new customer segment and aggressively usher as many of their free users as they could towards a paid plan.

These stories leave a lesson and a question in their wake.

The lesson, Ruben Gamez sums up succinctly: "Obviously free plans have worked well for companies like Wufoo, MailChimp, and FreshBooks, so we know they can work. But the problem is that we're not them. We need to stop blindly copying them and start thinking about ways to bring in revenue."

The question: Could thinking in systems have helped these companies identify the growth levers that ended up working for them faster?

How to experiment with growth levers faster

That businesses have had varying degrees of success with Freemium is as crystal clear an illustration as I can hope for: growth levers like Freemium are only as good as the patterns they are creating in your growth system (or subsystem).

The key to creating growth with growth levers, in light of this, seems to be: how effectively and how quickly you can experiment with patterns, move on from ones that aren't working, and ramp up ones that are.

If Baremetrics, Ning, and Bidsketch could have run faster acquisition, monetization, and retention experiments, they might have caught on that Freemium wasn't working for them earlier than they did. Better yet, they could ramped down on patterns that were not working and sidestepped freemium altogether.

The problem is that experimenting with patterns is difficult. Extremely difficult is you're working with large teams, complex tools, and droves of customers.

The problem: Long, unexpected loops create slow, eccentric experiments

"Too often, when people think of growth, they say 'I could dial up leads' and 'I can hire sales people'. They don't think of all the other things that go into operationally supporting those leads, converting that revenue, and carrying that revenue successfully forward."

— Suneet Bhatt, Chief Growth Officer, Help Scout

Let's stick with Bidsketch a little longer. Say, theoretically, Ruben is experimenting with a coupon to boost his conversion rates from freemium to paid.

Let's say he wants to offer his highly engaged users a discount to sign up for a paid plan.

Apart from the direct coupon calls he has to make (how large the discount ought to be, how long it should last), he also has to decide what tool he can use to run the experiment as quickly and as effectively as he can. After all, this coupon experiment is just one in many that he has (to try to find out if freemium is working for him or not).

Let's say he chooses a coupon management system to get his coupon off the ground — 'it will help me send out the coupon to the segment I want, track usage, and assimilate learnings', he thinks.

He's right. It will.

The problem, he realizes as he's evaluating coupon management systems, is all the code he has to write to tie coupons back to his subscriptions.

If Julie uses the coupon he sends her, her subscription information will have to be changed, her invoices will have to reflect the coupon, and her adjusted numbers will have to reflect in the monthly reports.

Can the code be avoided?

It will depend, he realizes, on how well he can set up a back and forth between Julie's customer account, his billing system, his coupon management system, his reporting system, and his accounting system.

There is a long, unexpected loop between sending the coupon out and actually feeding the changes it causes back into his subscriptions.

The solution: automate, automate, automate

The problem with long loops is that they inevitably mean slower experiments.

It's going to take that much longer to see if this coupon experiment is working if Ruben has to put all that effort into making sure that his subscriptions can keep up with the changes.

The same holds for experiments that you run in your subsystems — there is effort that you need to put in to close the loops on each of them.

The answer to long loops is better automation.

Imagine Ruben could send his coupon out without a second thought, with a tool that would close the loop without manual intervention.

Better automation can be more than the facilitator of experiments, it can be the usher of growth.

Now, there are many tools that can automate processes for you so you're looking at smaller loops and faster experiments — help desks help close the loop on customer requests, marketing automation software helps close the loop on the buyer's journey.

The rest of this guide will make a case for how one of these tools — a billing platform — can help close the loop on experiments across acquisition, activation, monetization, and retention.

Why billing platforms, though?

Four reasons:

It's reach in product and pricing: Imagine Mark's subscription renews on the first of every month. But he wants an upgrade to a higher paying plan immediately, the fifteenth. When do you charge him? And how?

It's impossible to figure out what your options are without considering what your billing platform can and can't support. Does it support changing the renewal date of an existing subscription? Does it support prorating the upgrade, if you want to continue billing Mark on the first? Did you build your product with volume or tiered pricing in mind?

Billing questions are subscription questions in disguise. Subscription questions are product and customer experience questions in disguise.

It's reach in customer care: If you've ever had the words 'technical difficulty' ruin your experience of something, you know how important this question is to the online business.

Hopefully, your billing platform kicks in to do some immediate customer care. Inform (with an in-app notification) why the payment might have failed, retry the card in case of a technical difficulty, and modify the subscription in case all efforts at recovery lead to nothing.

It's reach in analytics and reporting: Changes to subscriptions affect billing cycles, which in turn, affect the formulae you are using to calculate metrics, potential bugs in your reporting code, and the kind of metrics that it makes sense to track at the time.

It's reach in accounting and finance management: The connections between billing and accounting are similarly intricate. Between figuring out how much revenue you can recognize each month balanced against your CAC, reconciling payments made from your website with gateway and bank statements, and figuring out what tax you are liable to in every geography you have a presence in, clean books aren't possible without consistent, timely, and accurate information from your billing platform.

Given this kind of reach, a billing platform can close the long loop on an acquisition experiment like coupons.

For Ruben, a billing platform is exactly what he needs for faster experiments. It can segment the customers he wants to send the coupon to, track how many people use it, and rather than end the chapter there, go a step further — change the subscriptions of people who use the coupon, alter the charge on their invoices, and factor the changes into reports.

Here's what we've covered so far, in point form:

- Unhacking growth is seeing growth as more than an isolated strategy, hack, or blueprint. It is seeing it as a system. A system creates patterns of behavior. The upshot of thinking of growth as a system is that you can use it to create patterns of growth behavior.

- Growth levers are a powerful tool that you can 'leverage' for growth. The key to successful implementation is to pick the right lever for your growth system (picking the wrong one can lead to deadly results).

- How do you find the right one? Two ways: you can look at existing patterns and figure out what's working. Or you can implement a lever that's worked for someone else by creating patterns in your own growth system that can drive it.

- The key to growth, in light of these three points, seems to be experimenting with patterns as fast as you can. This can be difficult though - patterns in SaaS businesses come with loops that are hard to close (how they will tie back to your subscription and customer experience).

- You can experiment with patterns faster by automating as much as you can in your business. The upshot of this is you can initiate a pattern without worrying about the loop.

- In this regard, a billing platform can enable better automation, faster experiments, and more growth levers.

This section builds on how this is possible. It lays out how a billing platform impacts your customer lifecycle and how it might enable patterns and growth levers.

I would go so far as to argue that without these features your billing platform is standing in the way of your identifying which growth levers are working for you, and so impeding your growth.

Acquisition

[An external billing platform] has easily contributed to a third of our conversions. They've truly helped us open up to the global market, and drastically reduced our development cycles.

— Fred Stutzman, Freedom

The patterns that you build in the initial touchpoints that your customers have with your company can greatly affect how many of them give your product a shot. A billing platform can help you experiment with activation by allowing for

- Coupon management, so you can experiment with patterns around promotions, retarget customers who visited your pricing page and left, and discounts on your pricing or checkout page.

- Additional payment options, so you can experiment with customer segments and geographies. Alipay and UnionPay are incredibly popular in Asian markets, while most of Europe prefers direct debit over using a credit card like customers from the US and Canada.

- Experiments around your checkout pages, so you can optimize them for better conversion. From security seals, to the essential details you need to collect, and the right redirect after checkout is over. Here are a few checkout page tactics that you can try on for size.

- Experiments with patterns around trial — from how long your trials are (businesses with annual plans have discovered that longer trials convert better than shorter ones, B2B business have shorter trial rates than their B2C counterparts) to whether you can accommodate a customer who asks for an extension or provide a paid add-on service mid-trial. This could make or break the freemium model (if you're trying that growth lever out).

Activation and Retention

If your activation patterns are working, there's no doubt that they'll contribute to your retention. A huge part of retention, however, is playing with the patterns that allow you to build better relationships with your customers.

Your billing platform, tasked with sending out transaction communication, and ushering a customer through the checkout experience, can initiate beginnings. The median click-through rate for transactional emails is an astounding 4.3%, that's three times higher than the median for non-transactional emails (1.6%). It makes sense to leverage them, or at least experiment with the pattern.

Your billing platform can also enable experiments with patterns around

- A self-management customer portal that allows your customers to manage their subscriptions by themselves, increasing the amount of control they have over changes and translating to a better customer experience.

- Multiple currencies and multiple languages. If you're selling in different countries, communicating with your customers in their own languages will help you experiment with localization as a growth lever to build powerful word of mouth.

- Customizable invoices and bank statements go a long way as well. Customizing bank statements so your customers can associate their payments to you with your logo or your headline help build your brand in their minds. Invoices that are crystal clear about tax and subscription changes build trust.

- Most importantly, the subscription flexibility that your billing platform affords will help you experiment with customer requests — whether it's for an additional payment method, an add-on service in the middle of a subscription term, or the ability to pause and resume a subscription at will.

Revenue and Monetization

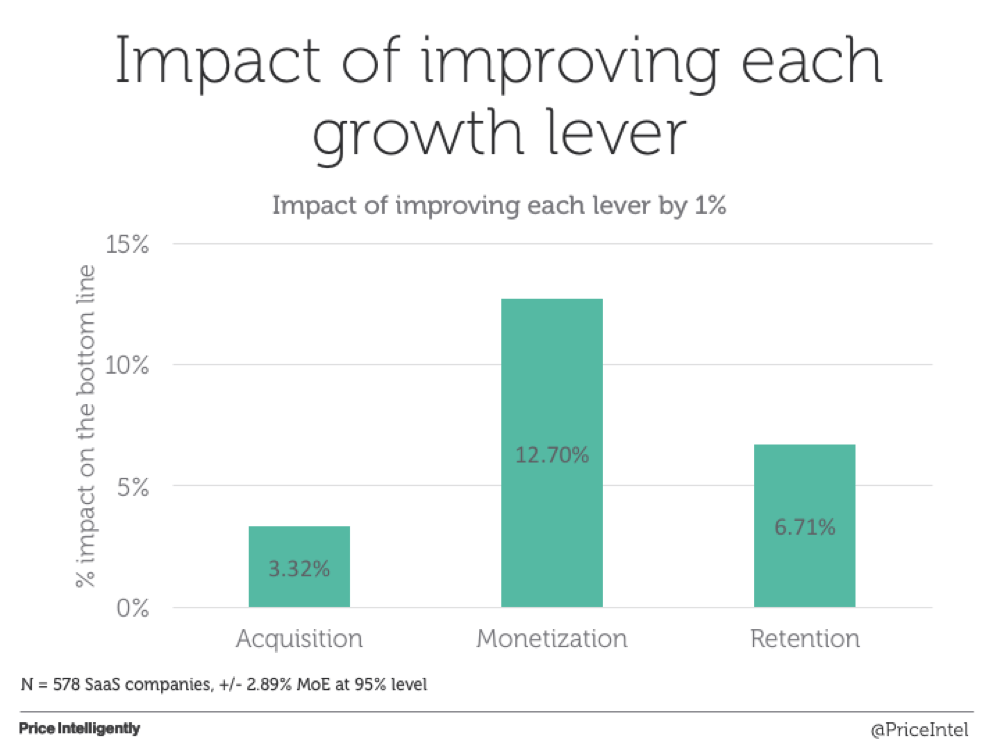

Finally, and most importantly (as PriceIntelligently's chart suggests), your billing platform can help you experiment with your revenue and pricing patterns. Not to mention the revenue that you recover with your billing platform will have huge impacts on your involuntary churn. Every attempt at recovering a payment that has slipped through the cracks results in another happy customer that didn't have to go out of their way to pay you.

- Pre-dunning emails help you catch failed payments before they happen. They're also useful if you want to experiment with building relationships or upselling.

- Grandfathering plans allows you to experiment with pricing models so your existing customers aren't affected by the changes.

- Dunning, or trying an alternative payment method after it fails, is a revenue recovery tactic that drives revenue and retention, a must for companies looking to experiment with patterns around their failed payments.

- Backup gateways sidestep issues that you might have with your payment gateway so that 'technical difficulties' are never the cause of your failed payments. You can also use them to experiment with different geographies and currencies, like using a particular gateway for a particular currency so that your accounting is smoother and the numbers are easier to categorize in your accounting system.

- Advance invoices allow you to collect money from your customers upfront, allowing you to experiment with cash flow and revenue needs that will accelerate other functions within your business that are working well.

- Fraud filters enable experiments with prepaid cards (you can blacklist them if you see that they're failing more than credit or debit cards), they allow you to experiment with payment limits, accepting customers from certain geographies, and catching non-payments and chargebacks before they happen.

Conclusion — perfect systems don't exist

The world is nonlinear. Trying to make it linear for our mathematical or administrative convenience is not usually a good idea even when feasible, and it is rarely feasible.

— Donella Meadows, Thinking in Systems

Thinking about growth as a system can be extremely beneficial to your business. It offers a framework for how to build patterns (within each pillar of your customer lifecycle), how to identify growth levers, and how to make sure that all the tools you are using (especially your billing platform) are helping you get the most out of them (with better patterns).

Systems are not a perfect model, though.

There's no such thing as the perfect system.

There are limits to organization, boundaries to connection, zany randomness that you may never see coming, nonlinear customer patterns that you will not be able to account for, and threats to team efficiency that can topple something that's working.

Yet, systems can surprise us.

Baked into the way they are modelled is the idea of a feedback loop. There might be limits to how resilient the elements in your growth system can be to a disruptive event like a member of your team leaving, or sudden, massive change in the market, but if they are communicating — if one part of your system is responding to what happens in another — there is hope for recovery.

As is the idea of evolution. As long as the interconnections exist, the way the elements in a system are connected can change and evolve. Patterns that result can change and evolve, growth levers can evolve too. Nothing is set in stone. The upshot of thinking in systems is that the interconnections will force you to see evolution across elements rather than in silos.

Finally, systems help put time in perspective. There's no way to start out with growth levers to leverage. And that's okay. SaaS growth takes time (considerably less than a regular business, admittedly, but time nonetheless). Systems take time to get off the ground, and experimenting to get in the air. Seeing all the elements and connections together will put that time in perspective so you don't expect the world too soon.

As Suneet Bhatt reiterates again and again, the perfect growth curve does not exist.

Systems might not be a perfect model. But what model is?